Resale is booming – but only the right brands should touch it

Fashion brands are moving resale in-house, turning nostalgia and sustainability into new revenue streams. But not everyone can (or should) play this game

Welcome to TOMORROW WILL ARRIVE, a platform for cultural critique and future thinking; offering perspectives on luxury, brand strategy, identity and design. Created by BIRCH, we are a London-based creative studio, founded in 2009. You can reach us here, or join our Subscriber chat here.

This piece began with a LinkedIn post. The claim: Ralph Lauren’s resale platform has quietly become a half-billion-dollar business, now representing seven per cent of total revenue and growing at 100 per cent annually. These numbers raised our eyebrows in the studio – such scale seems unlikely, and no official sources (that we have found) back up this claim.

But whether or not the headline is accurate, the point is still worth exploring.

Ralph Lauren has invested heavily in resale in recent seasons, and in doing so, has crystallised a broader trend: brands are no longer content to watch second-hand markets happen around them. They want to own the story, control the channel and profit from their past.

Resale, in other words, is moving in-house. And for some brands, it’s working.

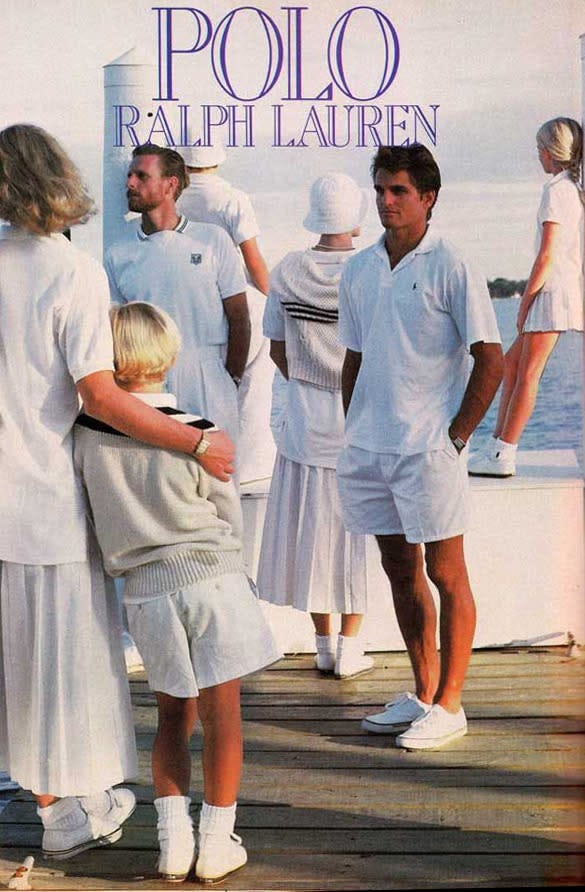

Ralph Lauren: Glamour in the patina

The strategy is deceptively simple. Ralph Lauren buys back pieces from its own history – hunting vests, faded Rugby shirts, iconic outerwear – that might sell for under $100 on eBay, and re-lists them at a hefty premium.

And they sell.

Why? Because the same item in a peer-to-peer listing is just “used clothing.” Artfully presented by Ralph Lauren, it becomes archival, authenticated and contextualised – shot in the brand’s visual language. It’s no longer second-hand, it’s a hard-to-find slice of heritage.

Taste-level factors into this too. If, like me, you prefer buying old Ralph Lauren to the new stuff, you’ll know that eBay and Vinted are littered with hundreds of pairs of beige ‘Andrew pant’ chinos and Polo tweed sports jackets, but only a handful of these are special pieces – from the brand’s high points in the late 70s, 80s and early 90s. Rare, made-in-USA pieces from these eras generate the most demand.

There are dealers – Thoroughbred New York is one of the most interesting – that specialise in vintage Ralph Lauren and know the brand’s various signatures well. But, ultimately, no one knows Ralph Lauren, like Ralph Lauren. Monetising this through curated edits of ‘special’ vintage pieces is a great move.

Especially given the brand’s sustained upward trajectory – its consistently strong results reported by BoF, among others, suggest the brand is hitting all the right notes, in today’s ‘commercial luxury’ climate.

Ultimately, this resale strategy is sound because “faded Americana” is not a trend for Ralph Lauren; it is the brand’s foundation. From Ivy League button-downs to frayed cowboy jackets, the label has always romanticised hard-working American icons that look like they’ve already lived a life. Resale is simply another stage on which Ralph Lauren can replay its mythologies.

It may not be generating half-a-billion dollars, but it adds prestige. And, let’s not forget, plays neatly into the brand’s sustainability strategy too.

Patagonia: Circularity as credibility

With sustainability in mind, Patagonia’s Worn Wear programme takes a different tack. Launched in 2017, it allows customers to trade in used pieces for credit, have them refurbished and buy them back through a clean, branded channel.

Here, resale isn’t romanticised; it’s operationalised. Worn Wear is less about scarcity and more about sustainability. It reinforces Patagonia’s identity as the brand that tells you not to buy unless you need to, the brand that truly wants your jacket to last a lifetime.

Over its lifetime, the programme has reportedly repaired more than 500,000 garments – all through the Worn Wear platform with a quality guarantee in place – a significant investment in time, resource and brand experience.

This said, resale is still a small portion of Patagonia’s revenue – around one per cent – but strategically it is enormous. Worn Wear cements Patagonia’s authenticity in sustainability and ensures that its circularity message is backed by infrastructure.

Lacoste: Testing the waters

Lacoste’s Seconde Main resale platform is a more recent entrant. Customers can resell Lacoste pieces or shop pre-owned within a branded environment that mirrors the polish of the mainline.

For Lacoste, this isn’t about scarcity or even, explicitly, sustainability. The crocodile has always thrived on ubiquity: polos, tennis sweaters, accessible sportswear that passes easily across generations. Resale here says: your 10-year-old Lacoste polo and your brand-new one belong to the same continuum.

It’s a smart statement about Lacoste’s inclusivity as a brand, not its exclusivity.

The rule of DNA

What unites Ralph Lauren, Patagonia and Lacoste isn’t a resale playbook. It’s brand DNA:

– Ralph Lauren can do resale because vintage glamour is embedded in its mythos.

– Patagonia can do resale because circularity is its mission, not a bolt-on.

– Lacoste can do resale because accessibility ket to its brand story, not a dilution of that story.

This, we think, is key: Resale only works when it deepens what the brand already stands for.

This is why Hermès, for example, takes such a dim view of resale and the Birkin second-hand market. The Birkin thrives on scarcity, mystery and the ritual of waiting. To legitimise resale would be to weaken the very aura that sustains it.

The broader picture

Other brands are experimenting too. Gucci Vintage (the successor to Gucci Vault) is a “shoppable digital museum” to retail rare archival pieces. Levi’s SecondHand programme reportedly saves 80 per cent of the CO2 of new denim and ties resale to trade-in credits. Hugo Boss’s occasional Pre-Loved drops fold surplus fabric reuse into a resale platform.

But the logic remains the same: resale is not about old clothes, it’s about brand authorship. Who gets to decide what the past is worth – the brand, or the marketplace?

Closing thought

Resale is no longer secondary. It’s becoming a platform for brand values, a loyalty driver and in some cases, a source of meaningful revenue. But it is not universal. Done well, it’s brand theatre; done poorly, it risks brand dilution.

Our advice: Use it to amplify the story a brand has always told – whether that’s faded glamour, radical sustainability, or sporty accessibility. Don’t use it as a means to hop on the bandwagon. Remember, authenticity in luxury is everything, and consumers can smell a cynical move a mile away.

For the right brands, though, resale is not second-hand. It’s timeless.